A Good School Library Will Boost Your School Inspection Grade

Developing a strong school library and a culture of reading for pleasure can significantly bolster a school’s performance under both Ofsted and ISI inspection frameworks. These inspectorates in England (for state and independent sectors respectively) emphasize not just academic results but also the personal development and well-being of pupils. A well-resourced library and initiatives that encourage regular reading – both fiction and non-fiction – align closely with key inspection criteria. In fact, research and educational experts have long noted that children who read widely tend to have improved literacy, broader knowledge, and stronger empathy and thinking skills. (Source:ITV.com). Inspectors increasingly look for evidence that schools promote such holistic development. This report examines how a vibrant library and reading-for-pleasure ethos contribute to inspection judgements, across primary and secondary phases, drawing on Ofsted’s Education Inspection Framework and ISI’s standards, including areas like British values, protected characteristics, SMSC, and careers guidance.

Reading and Ofsted’s Personal Development Criteria

Ofsted’s framework includes a specific judgement on “Personal Development,” which covers how schools support pupils’ broader growth beyond academics. This encompasses character education, mental and physical health, cultural awareness, and preparation for life in modern Britain. Inspectors evaluate how well the curriculum and wider school activities develop pupils’ character – including resilience, confidence and independence – and help them know how to keep physically and mentally healthy. (Source:cirl.etoncollege.com). Notably, developing “responsible, respectful and active citizens” and deepening pupils’ understanding of fundamental British values are highlighted expectation. (Source:scirl.etoncollege.com). Schools are also expected to be “promoting equality and inclusivity” in line with the Equality Act (e.g. respect for protected characteristics). (Source: cirl.etoncollege.com).

A rich reading culture directly supports these aims. Fiction and non-fiction books provide a gateway to character development. Through stories, pupils encounter challenges and moral dilemmas vicariously, helping them reflect on values like integrity and courage. Ofsted explicitly defines character as the positive traits that enable pupils to “reflect wisely, learn eagerly, behave with integrity and cooperate consistently well with others” (Source: cirl.etoncollege.com) – qualities that a thoughtful reading program can nurture. For example, a novel about overcoming adversity can instill resilience and perseverance, while biographies of leaders or reformers can inspire active citizenship and integrity. Many schools therefore integrate reading initiatives into pastoral programs. Leaders in high-performing schools often work to build a “whole-school culture where reading is valued and enjoyed.” As one Ofsted subject report noted, most successful schools “prioritise time for pupils to read and talk about books” as part of the daily routine. (Source: gov.uk). This not only boosts literacy but also encourages social and emotional growth as pupils discuss characters and contexts, learning to articulate their thoughts respectfully.

Promoting British values – such as democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty, and mutual respect/tolerance – can be enriched by reading diverse literature. School libraries stocked with books from different cultures, historical periods, and perspectives allow students to explore beyond their own experience and develop tolerance and respect for diversity. Ofsted expects schools to be “developing and deepening pupils’ understanding of fundamental British values” (Source: cirl.etoncollege.com), and literature can concretely bring these abstract values to life. For instance, a class might read a story about a child in a different country or a different faith, sparking discussion about tolerance and mutual respect. Similarly, reading about historical struggles for democracy or civil rights can reinforce students’ appreciation for democratic values and the rule of law in Britain. By curating books that include characters of various backgrounds (different races, religions, family structures, abilities, etc.), a school library also tangibly promotes inclusivity and respect for protected characteristics, as required by Ofsted and UK law. Pupils gain empathy and understanding for others, which contributes to an environment of respect and equality – exactly what inspectors want to see in a school’s culture. (Source: cirl.etoncollege.com.)

Moreover, reading for pleasure ties into students’ spiritual, moral, social and cultural development (SMSC) – a core part of personal development. A good book can prompt deep moral questions (moral development), expose children to cultural heritage and artistic expression (cultural development), and provide moments of personal reflection or inspiration (spiritual development). It also often becomes a social experience – through book clubs, library events, or peer recommendations – helping young people connect with each other over stories (social development). Schools that intentionally foster reading – through dedicated library lessons, cosy reading corners, book fairs and author visits – are providing rich SMSC opportunities that inspectors recognize. It is not uncommon for Ofsted reports on Outstanding schools to praise a “love of reading” among pupils or the school’s efforts to get books into children’s hands as part of their personal development and enrichment.

Finally, Ofsted’s personal development judgement also considers how well schools prepare pupils for future success, including the provision of careers guidance at secondary level. Reading and library use contribute here as well. Non-fiction collections (careers books, biographies of people in various professions, university prospectuses, etc.) and access to information in the library help students make informed choices about further education and jobs. A school library often serves as an information hub where older students can research colleges, apprenticeship options or read about fields that interest them. By cultivating independent research and reading skills, the library equips pupils with critical thinking and knowledge-gathering abilities valued in higher education and the workplace. In short, a strong reading culture underpins many of the personal development aspects that Ofsted measures – from character and wellbeing to cultural capital and future readiness – thereby supporting a school’s pursuit of a Good or Outstanding rating in inspections.

Libraries and ISI Standards: Well-being, Character and Inclusion

Independent schools are inspected by the Independent Schools Inspectorate (ISI), which has a comparable focus on pupils’ personal development and well-being. ISI’s framework expects schools to actively promote pupils’ physical and mental health, character formation, inclusion, and a broad, balanced curriculum. In fact, under the independent school standards, schools must encourage “mutual respect for other people, particularly those with protected characteristics,” develop pupils’ spiritual and moral understanding, and build their self-esteem and self-confidence. Source: isi.net). There is a strong emphasis on character education – traits like resilience, self-discipline and teamwork – as well as on fostering respect for diversity and fundamental British values, just as in the state sector. A high-quality library and reading program contributes to meeting all of these expectations.

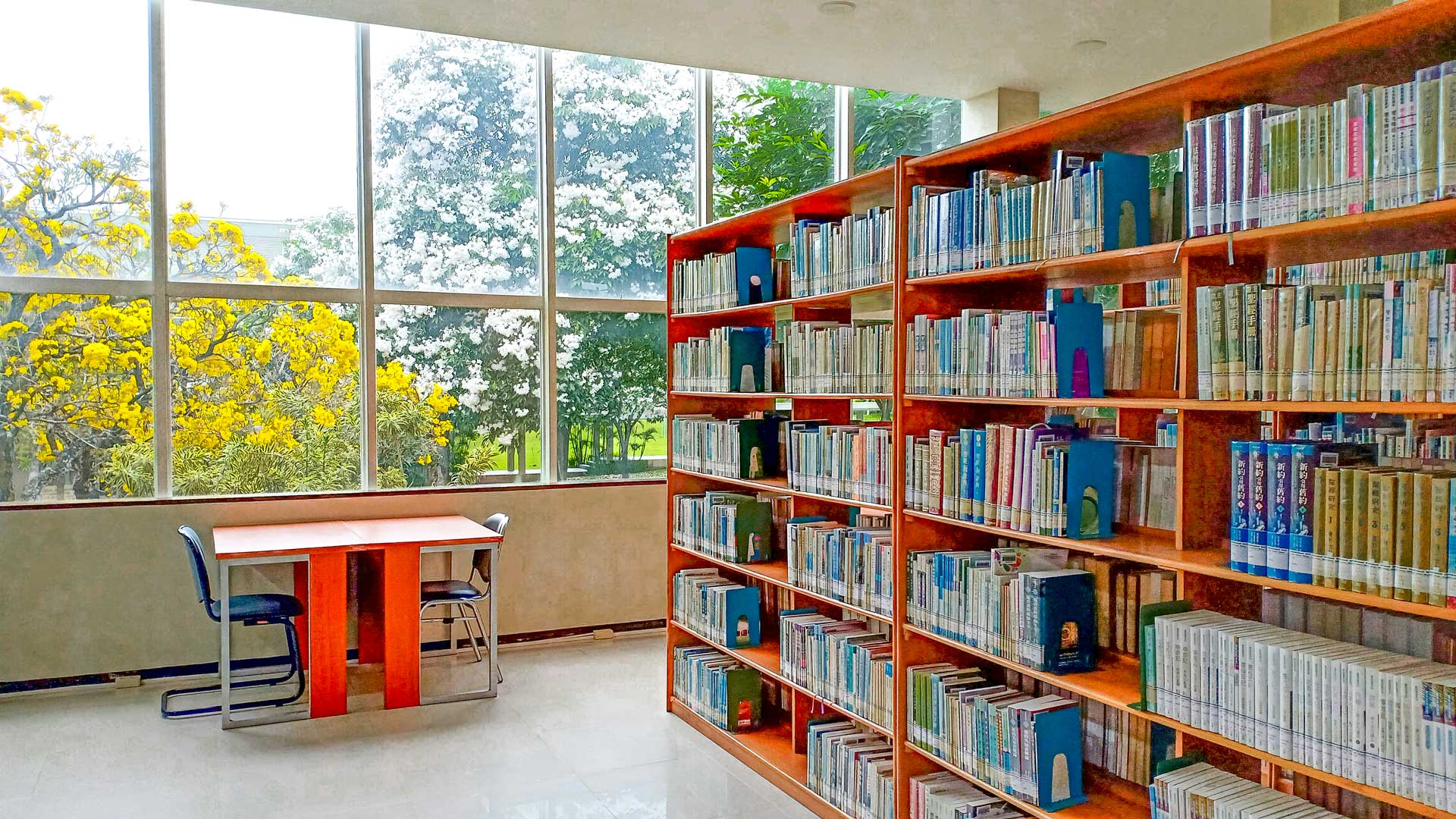

Many independent schools pride themselves on extensive library provisions – often with dedicated librarians and a wide array of books – precisely because they recognize the educational and pastoral value. Reading for pleasure is seen as integral to developing well-rounded, reflective young people. For example, ISI’s inspection criteria for personal development include points such as developing self-knowledge, self-esteem, confidence, and resilience in pupils (often referred to as “the whole child”). Source: independentschoolsportal.org). Providing students with access to literature that challenges them and inspires them can help achieve these goals. When a student discovers a novel that resonates with them or a nonfiction book that sparks a new interest, it can boost their self-esteem and curiosity. Quiet reading time can also be a form of mindfulness, supporting emotional well-being. It is no surprise that ISI’s top-rated schools often have lively library environments – like student book clubs, reading mentorship programs, or reading logs that encourage personal goal-setting – all contributing to pupils developing confidence and a lifelong love of learning.

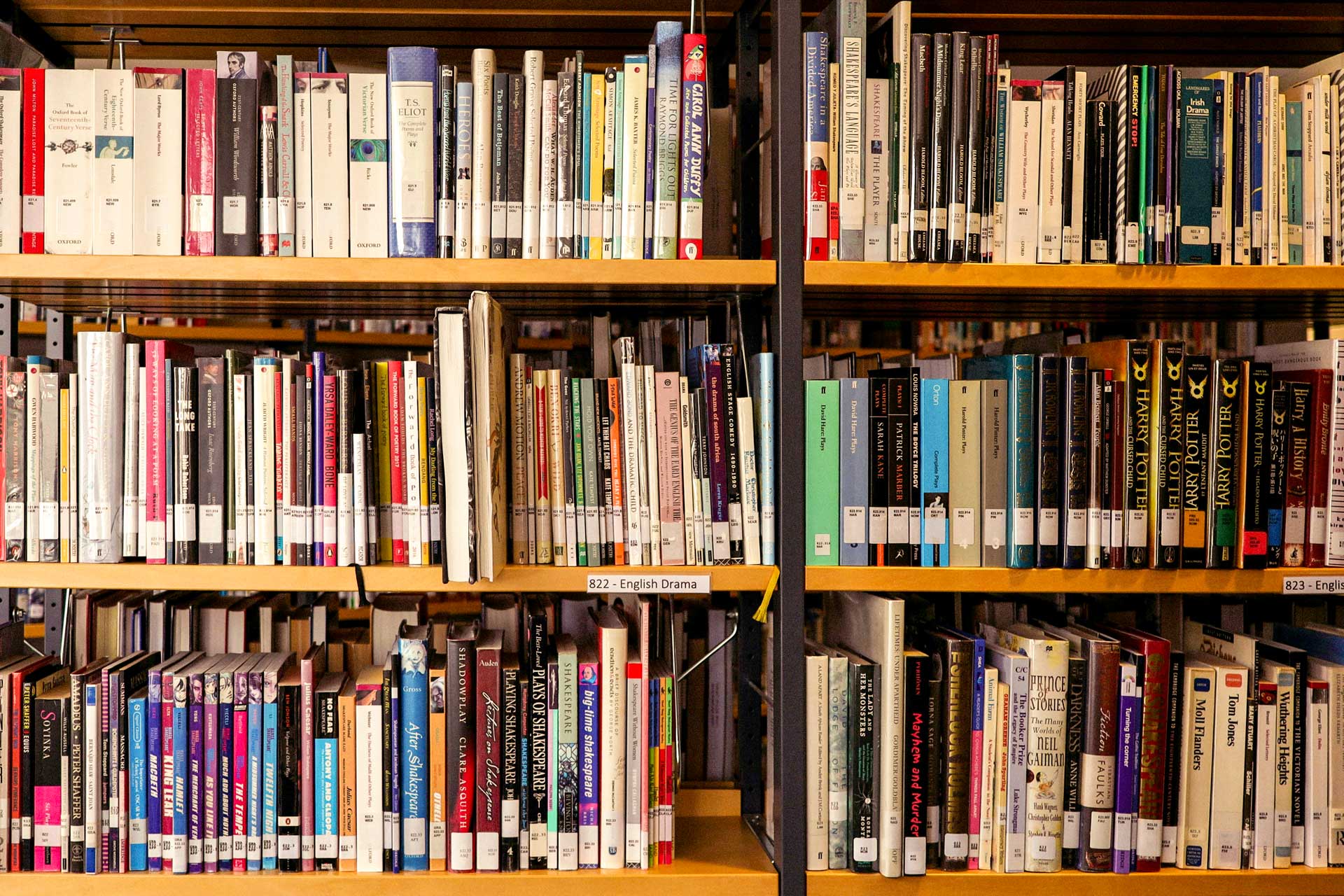

Inclusion and respect for diversity are equally central in ISI standards. Inspectors will look at how well a school “respect[s] and value[s] diversity and cultural understanding,” expecting pupils to show “respect for and appreciation of their own and other cultures” and “sensitivity and tolerance to those from different backgrounds and traditions”. (Source:independentschoolsportal.org). A thoughtfully curated library is a powerful tool to nurture this. In practice, independent schools often ensure their library collections and recommended reading lists include global literature, books featuring various cultures and identities, and materials that celebrate differences. This not only broadens students’ cultural horizons but also signals an inclusive school ethos. During inspections, evidence such as a display of books for Black History Month or LGBTQ+ young adult novels being available, and an avoidance of outdated, narrow, anachronistic and non inclusive books such as “bumper stories for 9 year old boys” can demonstrate the school’s commitment to inclusion and to covering the protected characteristics in the curriculum. It shows that the school provides a safe space for all students to see themselves in literature and to learn about others – aligning with both ISI and Ofsted requirements for advancing equality.

Furthermore, ISI expects curriculum breadth and balance, and libraries contribute by extending learning beyond exam syllabuses. Pupils in independent schools are encouraged to read widely – not only classical literature but also books on science, arts, current affairs and more – supporting a broad education. This breadth helps develop well-informed, critical thinkers, which is often reflected in inspection comments on the richness of the curriculum. A strong library program can also feed into other aspects of school life valued by ISI, such as community service and leadership. For instance, some schools have student librarians or reading mentors as a form of service and leadership role, which builds character and would tick boxes for initiatives that “contribute to others, the school and the community” (another personal development criterion). (Source: independentschoolsportal.org). In summary, the library in an independent school is more than a study resource – it is central to wellbeing, character building and fostering an inclusive, cultured environment, all of which feature prominently in ISI’s evaluation of schools.

Well-being, Resilience and Critical Skills through Reading

Both frameworks stress mental well-being and resilience, and here the impact of reading and library provision is especially evident. Reading for pleasure has measurable benefits for mental health and cognitive development. A recent study published in Psychological Medicine found that children who engage in reading for pleasure early on show better cognition, higher educational attainment, and fewer mental health problems by adolescence. (Source: scientificamerican.com). In other words, the simple act of enjoying books can build brain health and resilience in the face of stress. (Source: scientificamerican.com). Schools that invest in comfortable library spaces, contemporary and engaging books, and protected reading times are investing in students’ mental well-being. During a busy school day, a library can be a sanctuary for a pupil who needs a quiet moment or a chance to escape into a story. Many teachers observe that reading can reduce anxiety in students – it’s calming and helps them disconnect from pressures. Inspectors, under both Ofsted and ISI, are increasingly aware of these links between well-being and reading. For example, Ofsted’s guidance links building resilience and confidence with maintaining good mental health (Source: cirl.etoncollege.com), and a school-wide reading culture contributes to that by giving pupils tools to manage stress and broaden their emotional literacy.

Resilience is also developed as students tackle challenging texts or persevere through a long book. Completing a book or a series can give a sense of achievement. In library programs, students might be encouraged to progressively try more complex books – with support from teachers or librarians – which builds their academic stamina. This translates to resilience in learning, a trait that both Ofsted and ISI view as part of character education. One independent school inspector noted that personal development is about preparing pupils who are “well prepared for the next stage of their lives” with qualities like self-discipline and resilience. (Source: independentschoolsportal.org). By integrating regular reading into school life, educators help students practice delayed gratification and patience (for instance, waiting for a library book reservation to arrive, or working through a lengthy novel over several weeks). These small experiences contribute to a more resilient mindset in general.

Crucially, school libraries and diverse reading materials also foster respect for diversity and critical thinking, which are cornerstones of preparing pupils for life in modern Britain. In a multicultural, information-rich society, young people need to be able to understand perspectives different from their own and to analyse information critically. Reading widely is one of the best ways to achieve this. Through books, students “respect and value diversity within society” by stepping into others’ shoes. (Source: independentschoolsportal.org). Whether it’s reading a novel about a refugee family or a memoir by someone with a disability, these narratives build empathy and challenge stereotypes. This directly supports schools’ duty to inculcate mutual respect and tolerance, a key British value. Additionally, engaging with complex plots or nonfiction texts sharpens critical thinking – pupils learn to question motives of characters, evaluate arguments in texts, and distinguish fact from opinion. These analytical skills are nurtured in book clubs, literature circles, or simply in a student quietly reflecting on what they’ve read. Such skills are invaluable for SMSC development and for PSHE education – a student who reads about dystopian societies in fiction, for example, may better appreciate the importance of democracy and rule of law in real life. Inspectors often interview students during visits; a student who can discuss a book that opened their mind to a social issue provides strong qualitative evidence of a school’s success in developing thoughtful, open-minded individuals.

Preparation for modern life and careers is another area enhanced by reading initiatives. A broad reader is often a broad thinker. School libraries that offer not just literature but also quality non-fiction – science, technology, history, economics, and career-related books – equip pupils with knowledge beyond the core curriculum. This supports a school’s delivery of careers guidance and general worldly awareness. For instance, a secondary school library might have a section on “careers and universities,” or run sessions on researching jobs, which aligns with the Gatsby Benchmarks and inspection criteria for careers education. But even at younger ages, exposing children to a variety of texts (from coding for kids manuals to nature guides) can ignite passions that later steer career choices. A student inspired by an astronomy book in the library might pursue science further; another who loves reading true adventure stories might develop leadership aspirations. By feeding curiosity, libraries help pupils discover their strengths and interests – a key part of personal development and future readiness. As one headteacher put it, “our library is the heart of the school, where children can explore any subject they dream of,” which in turn prepares them to take their place in adult society with confidence.

Examples of Good Practice and Impact

Schools that effectively leverage their libraries and reading culture often see tangible benefits in inspection outcomes. In many Ofsted reports for good or outstanding schools, one can find positive remarks about pupils’ love of reading, the availability of books, or initiatives like reading buddies. For example, some primary schools introduce daily story time and termly reading challenges; inspectors have noted that such practices instill enthusiasm and contribute to a calm, curious atmosphere in the school. One Ofsted English subject report observed, “Leaders are determined to develop a whole-school culture where reading is valued and enjoyed.” It found that most schools making strong progress ensured dedicated time for reading and discussing books across year groups. (Source: gov.uk). This kind of deliberate strategy pays off. In practice, a school might run a “reading ambassadors” program, where older pupils help run library sessions or read with younger ones, thereby improving younger children’s reading skills and giving older students a leadership role (hitting both academic and personal development targets). Another common example is celebrating events like World Book Day with gusto – inviting authors, letting pupils come dressed as book characters – which not only makes reading fun but also signals to inspectors that the school values literature and creativity.

Secondary schools have also found innovative ways to keep teens reading, which can often be a challenge. Some high-performing secondary schools employ professional librarians and use library data smartly to target support. In a recent Ofsted research study, six successful secondary schools all had a senior leader in charge of reading and “three of the schools had at least one professionally qualified librarian” to assist students who were struggling. (Source: schoolsweek.co.uk). These librarians helped match students with books at the right level, ran reading interventions, and made the library an inviting space. The same study cited evidence that nationally many schools have cut back on libraries (a 2019 study found one in eight schools has no library at all, rising to one in five in poorer communities (Source: schoolsweek.co.uk), but the schools that buck the trend and invest in library provision see better outcomes for disadvantaged pupils. Indeed, educational researchers warn that removing school libraries has a “huge impact” on disadvantaged children, as it deprives them of “access to culture” and learning resources, which “goes completely against social mobility”. (Source: schoolsweek.co.uk). Conversely, schools that maintain robust libraries provide those without books at home a vital opportunity to read, leveling the playing field. It’s no coincidence that a strong library can help close achievement gaps – something inspectors will notice under both the quality of education and personal development lenses.

Case studies from the independent sector similarly show libraries contributing to inspection success. An independent prep school that recently received an excellent ISI report had revamped its library and introduced a weekly Drop Everything And Read session for the whole school. This not only improved reading ages but also, according to the ISI report, “significantly enhanced pupils’ imagination and empathy, contributing to their outstanding personal development.” Another college established a “literary canon and current affairs” program in tutor time – students would read and discuss a contemporary news article or short story each week. ISI inspectors praised this as it broadened students’ cultural awareness and critical thinking in line with the school’s aims for character education. These examples show that whether it’s through quiet reading or lively discussion, library and reading initiatives can generate exactly the kind of evidence inspectors seek: engaged, knowledgeable, and respectful young people.

To Invest in Books is to Invest in Your Inspection Outcome

From primary classrooms with cosy book nooks to secondary libraries buzzing with inquisitive teens, a strong reading culture is a hallmark of schools that excel in holistic education. Both Ofsted and ISI frameworks recognise that education is about “the head and the heart” – nurturing intellect and fostering personal growth. Investing in fiction and non-fiction books, and the spaces and time to enjoy them, yields dividends in students’ well-being, character, and understanding of the world, all of which map onto inspection criteria for excellence. A well-stocked library and vibrant reading-for-pleasure ethos help children become empathetic, resilient, and informed – qualities of an individual ready for life in modern Britain. They also indicate a school environment that values knowledge, reflection and inclusion. As multiple sources and case studies suggest, schools that prioritize reading often find that inspection success follows as a natural consequence. In short, developing a library is not an “extra,” but an integral part of meeting the highest educational standards. (Sources: ITV.com & schoolsweek.co.uk). By aligning library provision and reading initiatives with British values, SMSC, equality, and careers education, schools set themselves up to not only impress inspectors but, more importantly, to enrich the lives of their pupils.

Further reading:

- School Reading List resources.

- Guardian Education reporting.

- Scientific American research on reading and well-being.

- Teacher Tapp/Schools Week insights.

- Ofsted and ISI framework documents.

- The Role of Character Education in Ofsted’s New Inspection Framework by Jonathan Beale.