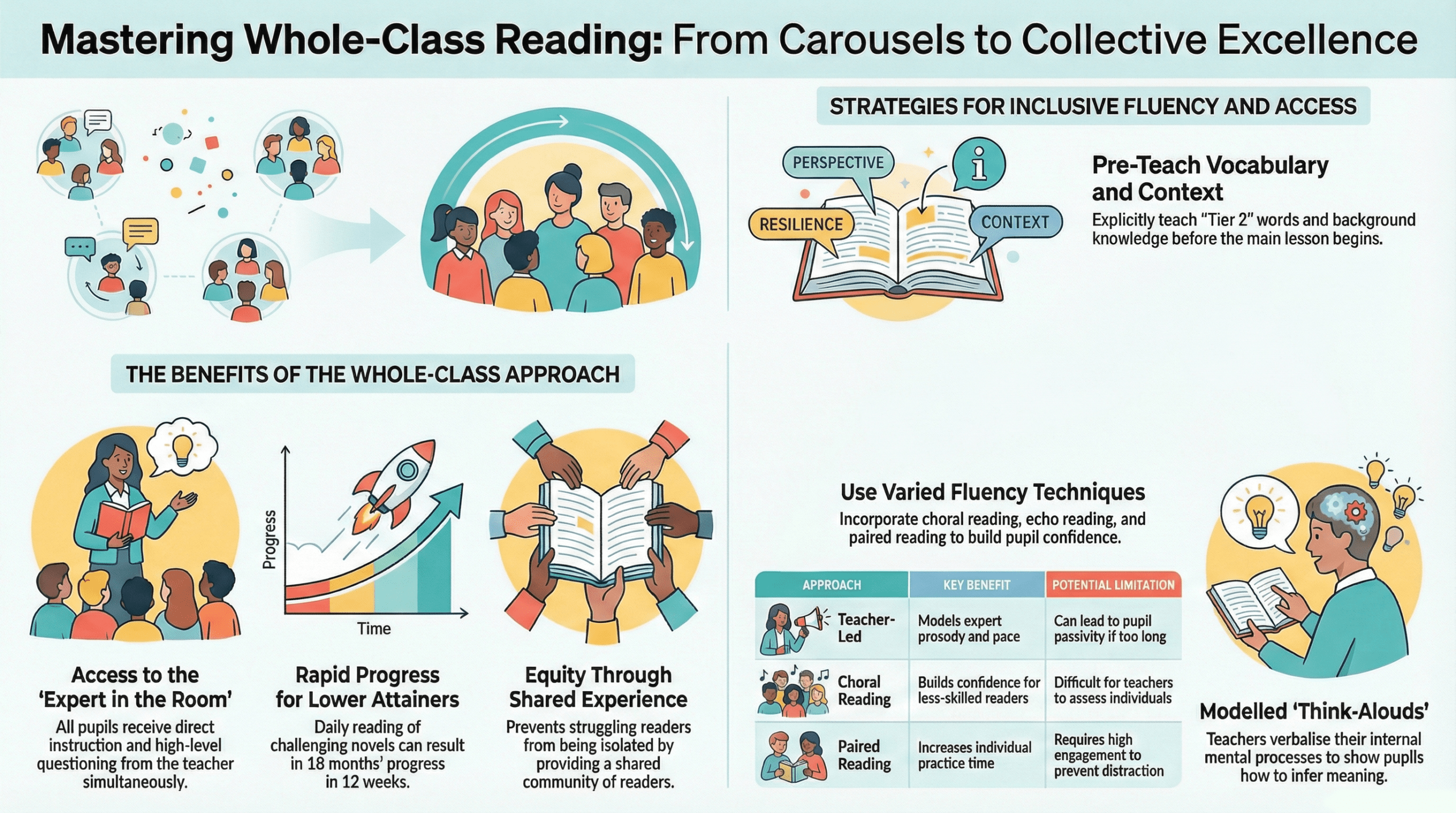

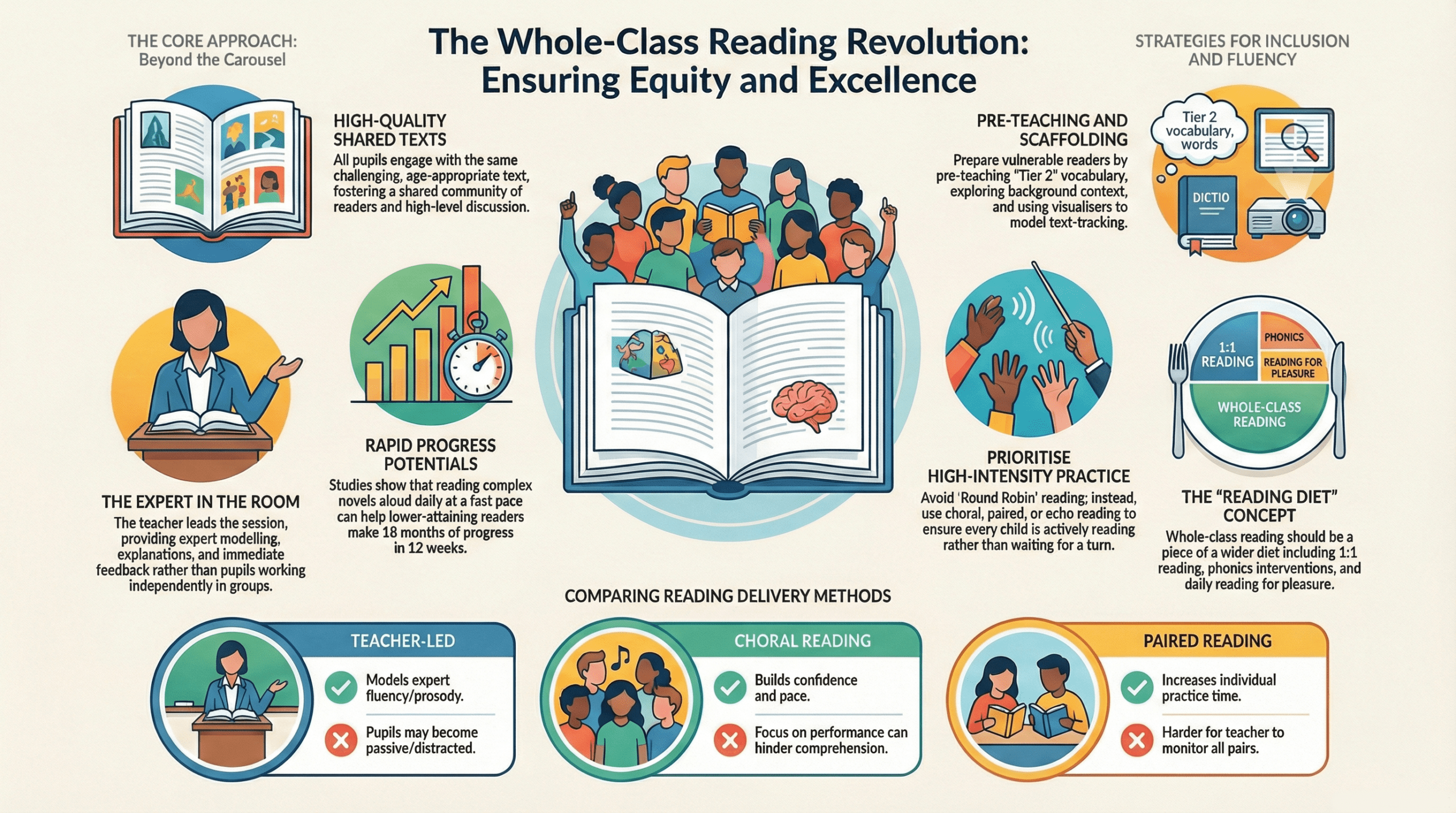

Whole-class reading (WCR) is back in fashion, but it usually arrives for a mundane reason: time. In a carousel system, many pupils get about 45 minutes of direct reading teaching a week; switch to a daily, teacher-led slot, and that can rise to roughly three hours and 45 minutes – enough time to build fluency, teach vocabulary, and talk about meaning without sprinting. What comes next is the part schools often underestimate: “everyone reads together” is not a method on its own, so the approach stands or falls on the plan – what pupils read, how much each pupil actually reads, how questioning and talk run, and what happens to children who cannot yet decode the shared text. Done well, it keeps comprehension, vocabulary and curriculum knowledge inside the reading lesson; done badly, it becomes slow turn-taking, long waits, and a lot of tracking with very little reading.

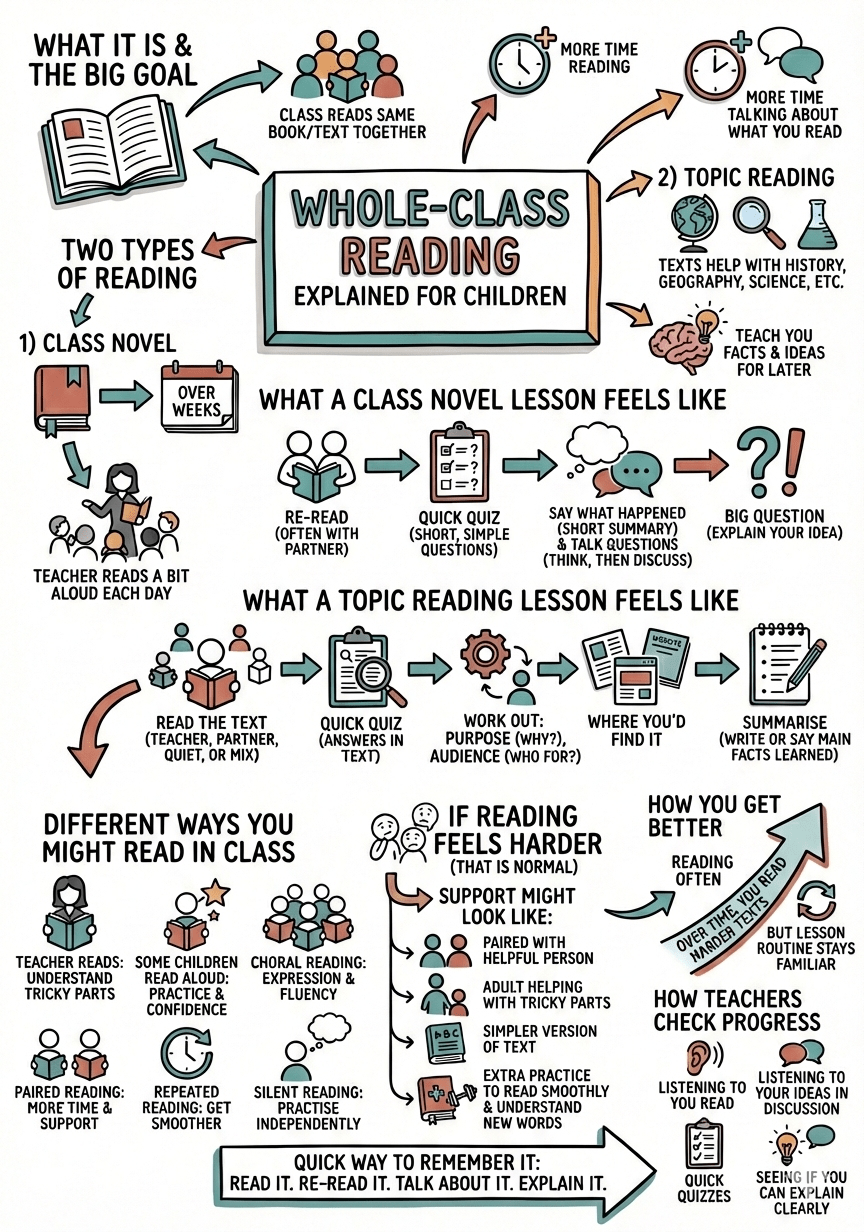

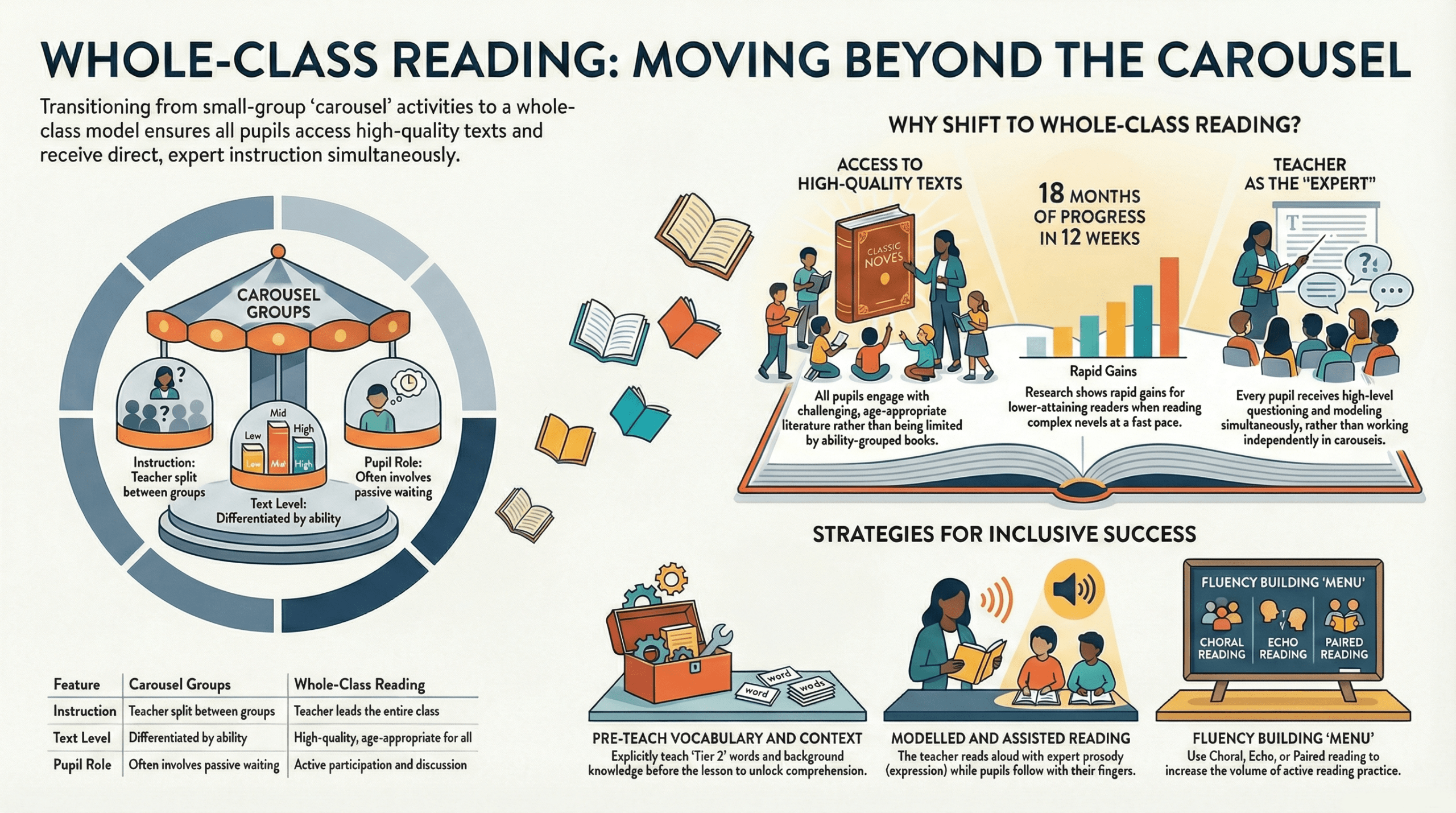

So what does whole-class reading do? Put simply, whole-class reading puts one text in front of the whole class, for one lesson, with the teacher steering the reading and the talk. Schools that move to this model often start with a time problem. A carousel approach can leave each pupil with roughly 45 minutes of reading instruction per week. A daily whole-class slot can take that up to around three hours and 45 minutes.

What changes when the class reads together

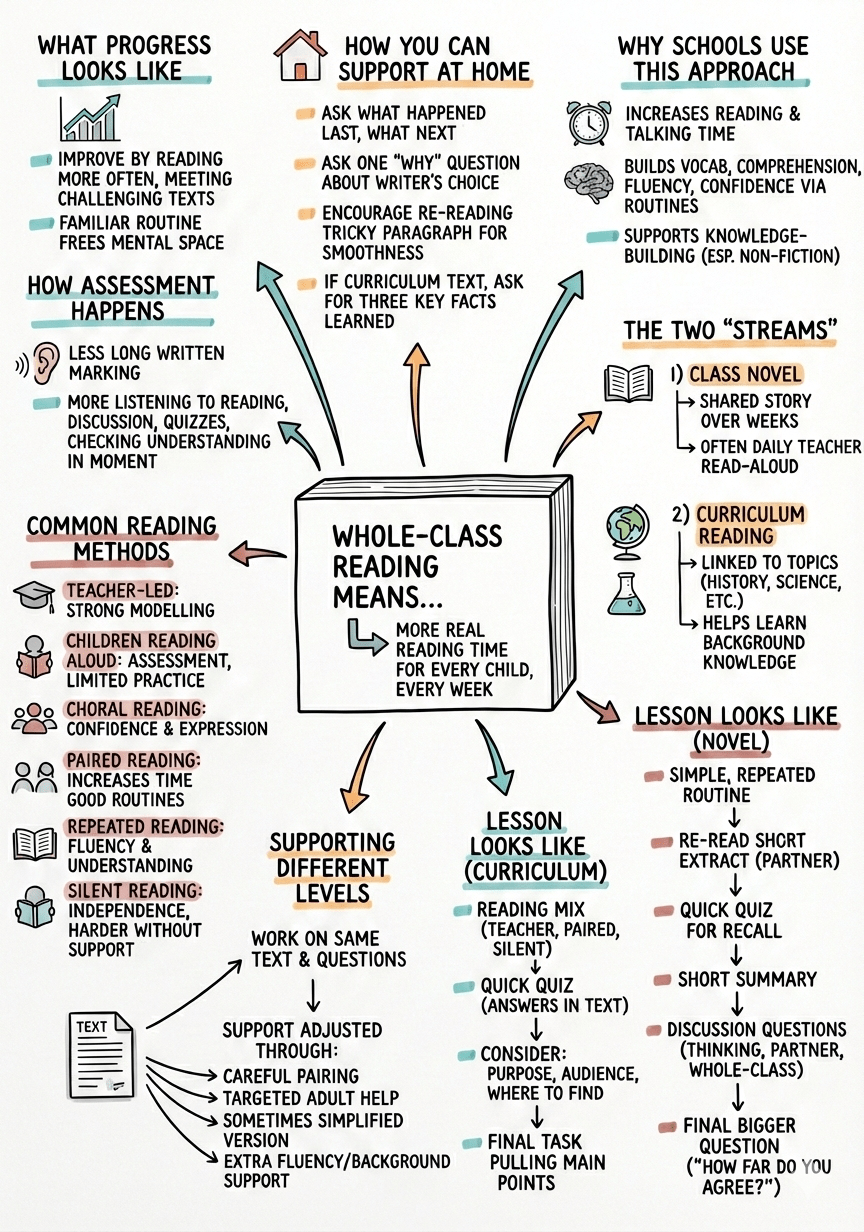

A whole-class lesson still needs a plan, because “everyone reads together” is not a method on its own. In many classrooms, the same set of building blocks comes up again and again: paired talk in mixed-attainment pairs; a shared text that sits beyond independent access for the strongest readers; teacher modelling of pace and phrasing; active pacing so the lesson does not drag; a mix of targeted checks and open questions; spoken answers that point to evidence in the text; and follow-up tasks that show what each pupil has understood, with small tweaks for support or challenge.

That lines up with the direction of England’s curriculum and guidance. The National Curriculum flags that pupils who cannot decode fluently face rising barriers to understanding and writing, while also stating that those pupils should still follow year-group study for listening, vocabulary, grammar, and discussion. The EEF’s Key Stage 2 literacy guidance sets out teaching for comprehension strategies and vocabulary, with practice that sits inside reading, not parked somewhere else.

A week that mixes a novel with subject texts

A common pattern uses five reading lessons of 45 minutes, plus a teacher read-aloud of the class novel for 12 to 15 minutes outside the reading lesson.

In that setup, two sessions often focus on the class novel, with the other three used for subject texts that feed into science, history, geography, or RE later in the day. The planning aim tends to be access. The class novel gives space for narrative, character, and language work. Subject texts build background knowledge and tiered vocabulary that connect directly to the curriculum. This taps into a familiar point from reading research: comprehension depends on language and knowledge, not reading strategies alone. EEF guidance keeps vocabulary and background knowledge at the centre of KS2 reading instruction.

Inside a class novel lesson

A novel lesson can start with the teacher reading for about 15 minutes, with every pupil following in their own copy. At the end, the teacher gives a short summary, then repeats a summary at the start of the next session, so pupils return to the text without missing links in the story.

A quick recall check can come next. One approach uses a short “quick quiz” written in a pupil book with a date and no lesson title. Year 3 might use around six questions. Year 6 might use around ten to twelve. The class marks it together. If a pupil gets stuck, staff offer choices so the lesson keeps moving and does not stall on one missing detail.

That quiz is not the comprehension work. It is a practical guard rail. It keeps the narrative thread in place so the class can talk about motive, viewpoint, language, and consequences without losing track of who did what and when. It also gives the teacher a daily signal on who has followed the reading.

Inside a “wider curriculum” reading lesson

Subject reading sessions often begin with a short set-up, followed by time to read for at least 20 minutes. Pupils who finish can reread sections, so some end up reading the same passage two or three times in a single lesson, which is usually where the meaning starts to stick.

One routine uses “popcorn” reading, where the teacher chooses who reads next, with modelling and feedback, and with some pupils not called on at all in that format.

This matters because one-at-a-time reading brings a trade-off that teachers feel quickly. One pupil reads aloud, everyone else tracks, so most pupils get limited minutes actually doing the reading out loud.

A framing task can then treat the text like something that exists in the real world, not a worksheet that fell out of the printer. Three fixed questions can sit at the front: what the text is for, who might read it, and where it might appear.

A second short quiz can follow, with answers taken in order and without full-sentence writing. The lesson can then finish with one longer response that shows what the pupil has understood from the passage and flags misconceptions before the later subject lesson.

Reading fluency sits under the whole model

Whole-class reading can easily slip into turn-taking, with long waits and very little reading practice for most pupils. A Teacher Tapp poll found that 45% of 1,674 respondents used some form of one-at-a-time reading.

Tim Shanahan’s critique of turn-taking reading comes back to intensity. Pupils need a high volume of practice to build fluency, so a model that hands each child a brief turn limits the amount of real reading they do. Better options increase reading volume, including paired reading with turns after each paragraph, choral reading, and repeated reading of the same passage.

That view fits with the wider evidence on guided oral reading. The US National Reading Panel reports that guided oral reading supports fluency and comprehension, unlike independent silent reading without guidance for pupils who still need support. Reviews of repeated reading also report gains in fluency and, in many studies, gains in comprehension, including for pupils with reading difficulties.

The classroom takeaway is simple. If fluency is the goal, pupils need routines where each one reads more than a few sentences across the lesson. Pair reading, choral reading, echo reading, and purposeful rereading all increase the number of words each pupil reads.

What happens to pupils who cannot yet decode the shared text

The hardest issue is access for pupils who sit well below the expected standard, including pupils who still need explicit word-reading instruction. The National Curriculum position in years 3 and 4 creates a dual duty: pupils need decoding support through a systematic phonics programme, and they should still take part in year-group listening and discussion.

In the lesson itself, support often starts with teacher modelling while pupils track the text, then moves into short echo reading, where the teacher reads a sentence or paragraph and pupils reread the same part. Teaching assistants can run the same routines one-to-one or in small groups during the whole-class lesson, using modelling and repeated reading to build fluency without pulling pupils away from the shared content.

Some adjustments sit outside the main session. A pupil might pre-read a passage before the class lesson so the text feels familiar when the whole class tackles it. Another option is a simplified version of the same passage, so the pupil can access the same ideas and then rejoin the discussion with the class. Some schools also use a “megatext” approach, where the same content is available at several reading levels, including versions created with AI tools to support access.

Whatever approach a school chooses, it needs a clear line between support and substitution. If the shared text becomes the only reading input and pupils below the text level never practise decoding, the gap stays put. If the shared text stays out of reach and pupils never properly enter the reading, language and knowledge stall too. The aim is two tracks running side by side: decoding teaching, alongside full participation in listening, discussion, and curriculum content.

Questioning, talk, and written response

Whole-class reading stands or falls on the questions. Targeted checks pick up misunderstandings before they settle in. Open questions push pupils to choose evidence and explain why it matters.

A useful routine is to get pupils to say their answers before they write them, with sentence stems that help them link a language choice to meaning. When it works, it stops the lesson from becoming “guess what the teacher wants” and keeps pupils anchored to the text, which is where the thinking needs to happen.

EEF guidance supports explicit teaching of comprehension strategies and structured discussion that keeps pupils anchored to the passage. Ofsted’s English subject reporting also places weight on fluency, vocabulary, and curriculum planning that makes reading part of the subject offer, not something bolted on at the edges.

Written work needs clear limits that hold up in a real timetable. If every reading lesson ends with a long piece of writing, the reading time disappears. If every lesson ends with the same worksheet sequence, whatever the text, pupils can get through it with minimal reading and strong compliance. A better balance is a short recall check, then one longer written response when it genuinely serves the lesson aim, so reading stays at the centre.

The silent reading question

Once pupils read fluently, more of the lesson can shift towards individual silent reading, with teacher input aimed at vocabulary, background knowledge, and discussion. Silent reading lets pupils move at their own pace and cover more text than a one-at-a-time format. It also makes rereading easier, because pupils can go back over a confusing sentence or paragraph straight away without waiting for a turn.

That does not mean teachers should drop shared reading altogether. Some passages are hard because of the ideas, the language, or both. In those cases, a teacher read-through with brief clarifications can get the class to understand more reliably, before pupils move into discussion and questioning. One workable sequence is simple: pupils talk in pairs about what they already know, the teacher reads and clarifies key vocabulary, then pupils return to the text through discussion and questions.

What teachers still need to decide

Whole-class reading is a framework, not a script. Teachers still decide which texts to use, how to balance teacher reading and pupil reading, when rereading matters, and when pupils should move from tracking the teacher to reading independently.

Schools also need to be honest about what they are trying to fix. Time sits at the top of the list. Access sits alongside it. Reading volume per pupil matters just as much, because pupils do not build fluency on tiny turns. When those three line up, whole-class reading can support curriculum learning, daily vocabulary exposure, and discussion that includes the full class, not only the group closest to the teacher.

Whole-class reading solves a timetable problem, but it only improves reading when schools treat it as teaching rather than a seating plan. The non-negotiables sit in plain sight: enough minutes for every pupil to read, routines that build fluency rather than ration it through turn-taking, questions that force attention back to the text, and practical support that adds decoding practice without cutting pupils off from year-group talk and knowledge. Get those decisions right, and the model earns its daily slot, because it keeps vocabulary, comprehension and curriculum content in the same lesson; get them wrong and the extra time disappears into slow pacing, low reading volume, and the familiar illusion that tracking a page counts as reading.

Resources and references

- Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) – Improving Literacy in Key Stage 2 (guidance report landing page)

- EEF – Improving Literacy in Key Stage 2 (second edition report PDF)

- Ofsted – Curriculum research review series: English.

- Ofsted – Telling the story: the English education subject report.

- Department for Education – National curriculum in England: English programmes of study.

- Department for Education – English programmes of study: key stages 1 and 2.

- Department for Education – The reading framework.

- National Reading Panel – Fluency chapter (guided oral reading and independent reading)

- Therrien, W.J. (2004) – Repeated reading meta-analysis.

- Kuhn, M.R. & Stahl, S.A. (2003) – Fluency review (Journal of Educational Psychology.

- Topping, K.J. (1987) – Peer tutored paired reading (Educational Psychology)

- Miller, D., Topping, K., & Thurston, A. (2010) – Peer tutoring in reading (British Journal of Educational Psychology)

- Topping, K. (2011) – Peer tutoring in reading in Scotland (large-scale randomised controlled trial)